FS Video Marshaller – Simulate Hand Signals Used by Real-World Pilots

FS Video Marshaller from FS2Crew recreates genuine ground crew instructions using authentic video technology, ensuring each pilot gesture…

From real-time aerodynamics to approximations driven by consumer hardware limits, flight simulators rely on carefully tuned flight models to create convincing aviation experiences. This article explains how modern platforms balance aerodynamic forces, numerical stability, hardware constraints, and modeling tradeoffs to emulate realistic performance. It also examines why different simulators feel distinct and the impact of add-ons on overall credibility.

Key takeaways:

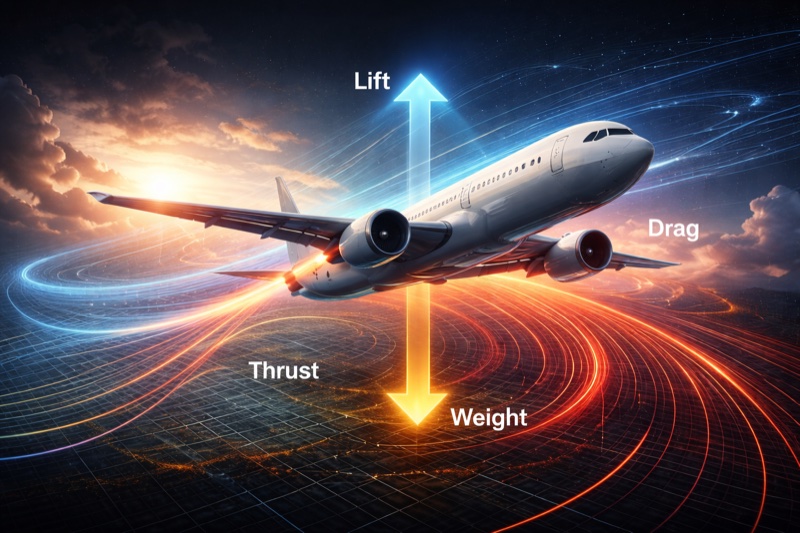

A flight model is the part of a simulator that translates pilot inputs and environmental conditions into aircraft motion. It estimates forces and moments—lift, drag, thrust, and weight—along with pitch, roll, and yaw behavior, then uses those to decide how the aircraft responds from one moment to the next. In simple terms, it’s the aircraft’s physics engine: given speed, angle of attack, control deflection, air density, and configuration, it determines what the airplane actually does.

That sounds straightforward until you realize what’s being compressed into that single phrase “physics engine.” In the real world, airflow over a wing is not a single number. It changes across the span, it separates and reattaches, it becomes turbulent, it interacts with propwash or jet exhaust, it’s distorted by the fuselage and landing gear, and it behaves differently during a steady climb than it does during a rapid pitch-up. A simulator has to turn that continuous, messy reality into stable numbers it can compute reliably many times per second.

So how do flight simulators simulate flight physics? At their core, they run a continuous real-time loop. The simulator samples the aircraft’s current state (position, velocity, attitude, angular rates, engine state, control surface positions), estimates aerodynamic and propulsion forces using simplified math models, and then integrates those forces forward in time to update position and attitude. This loop runs repeatedly while also driving instruments, autopilot logic, weather interaction, damage models, and visuals—often under tight CPU and timing constraints.

What’s important to understand is that consumer simulators rely on approximations, not full computational fluid dynamics (CFD). Most platforms use one or more of three broad approaches: lookup tables (precomputed aerodynamic coefficients across conditions), analytical or blade-element methods (dividing lifting surfaces into sections and estimating local forces), or hybrid systems that combine elements of both. In practice, “real-time, stable, tunable, and believable” usually wins over “maximally theoretical” on a home PC.

This is why platforms like Microsoft Flight Simulator, X-Plane, Prepar3D, and the older Flight Simulator X lineage can all produce convincing flight behavior while still feeling noticeably different once you’re in the cockpit. The headline method matters, but the details—data quality, numerical integration choices, control filtering, ground physics, and even camera behavior—often matter more.

Quick definitions (plain English):

“Realism” in flight simulation is a loaded word. People often talk about realism as if it’s a single knob, but what you perceive as realistic is a blend of physics, sensory cues, and how the simulator translates your hardware inputs into aircraft response. Two simulators can be equally defensible yet feel completely different depending on tuning choices and assumptions.

Modern lighting, photogrammetry, and ultra-detailed cockpits make motion look plausible almost by default. When the outside world sells speed, height, and depth cues convincingly, your brain often forgives subtle physical inaccuracies. That’s one reason debates about “flight model realism” tend to flare up whenever a simulator makes a big visual leap: graphics shift expectations more than most people realize.

There’s also a reverse effect: when visuals are less convincing, users may blame “physics” for what is actually a perception problem. A slightly stuttery frame cadence, a narrow field of view, or an overly rigid camera can make otherwise reasonable flight dynamics feel wrong—especially in turbulence or during flare and touchdown.

In a real aircraft, pilots perceive motion through far more than sight alone. Acceleration shows up in the vestibular system, seat pressure, control loading, peripheral vision, vibration, and sound. At a desktop, nearly all of that disappears. A simulator can be numerically faithful and still feel “off” simply because the pilot’s body isn’t receiving the cues it normally relies on.

To compensate, developers often introduce damping, input shaping, stability assists, and camera tuning. These tweaks can dramatically improve usability and reduce “twitchiness” from consumer controllers. But they also mean a simulator’s “feel” may be the result of deliberate filtering and cueing, not just raw aerodynamic computation.

Joystick curves, dead zones, frame pacing, and even monitor size all influence how stable or responsive an aircraft feels. Many users end up comparing a relatively raw response in one simulator to a heavily filtered setup in another without realizing it. If you’ve ever “fixed” a twitchy airplane by adjusting control sensitivity, you’ve already encountered an important truth: the control pipeline is part of the perceived flight model, even if it isn’t aerodynamics.

Hardware matters too. A short-throw joystick with a stiff centering spring encourages small, abrupt inputs. A longer-throw yoke provides more physical resolution. Rudder pedals dramatically change yaw control and crosswind landings. Even the difference between a smooth potentiometer and a high-resolution Hall sensor can be felt when trimming precisely or holding a narrow airspeed band.

Even the simplest credible flight model must balance forces and rotational effects in a believable way. Without diving into equations, here’s what every simulator has to represent conceptually:

What separates an “okay” flight model from a convincing one isn’t just having these forces—it’s how they interact across different conditions. Yaw-roll coupling, propwash over tail surfaces, trim response across speed, flap pitching moments, and configuration changes all reshape the force balance in ways that experienced pilots notice quickly.

Many “feel” arguments boil down to how a simulator handles inertia and energy. In a real airplane, energy management is everything: pitch trades airspeed for altitude, drag bleeds energy, and power restores it. A model that nails the basic lift curve but mishandles inertia, drag rise, or prop/jet response can feel oddly floaty or overly sticky because the aircraft doesn’t gain and lose energy the way you expect.

Similarly, rotational inertia matters. A heavy aircraft should not respond like a lightweight aerobatic trainer. Correct mass distribution affects roll acceleration, Dutch roll tendencies, pitch response to turbulence, and how quickly the aircraft damps out oscillations. These behaviors are often more noticeable than a small cruise-speed discrepancy.

High-fidelity CFD solves airflow across a three-dimensional mesh, capturing vortices, separation, and transient effects in detail. That kind of computation can consume enormous resources for a single flight condition. Doing it dozens or hundreds of times per second, for multiple aircraft, with weather, traffic, avionics, and rendering running alongside it, simply isn’t practical on consumer hardware.

Even if raw computing power were unlimited, there’s a second problem: CFD requires careful setup, grid resolution decisions, turbulence models, boundary conditions, and validation. It’s not a plug-and-play “make it real” button. For consumer simulators, the goal is not to solve fluid dynamics from scratch every frame—it’s to approximate flight behavior reliably and interactively.

Most simulators run physics at a fixed or semi-fixed tick rate—commonly in the tens to low hundreds of updates per second—while visuals render at whatever frame rate your GPU can sustain. When frame rate fluctuates, the physics must remain stable and predictable. That requirement alone pushes engines toward models that behave well under discrete time steps.

Tick rates also interact with control feel. If the physics loop is slow or inconsistent, inputs can feel laggy or “steppy.” If it’s fast but noisy, the aircraft can jitter. A lot of the engineering work in a flight model is not just “compute forces,” but “compute forces that remain stable under real-world PC performance variability.”

Flight dynamics don’t run in isolation. They compete with avionics, systems simulation, weather, AI traffic, and scenery streaming. Even when the GPU appears underutilized, many flight-model calculations are CPU-bound and latency-sensitive. Raw compute power isn’t the only limit—timing is just as critical.

This is also why complex aircraft add-ons sometimes stress the simulator in surprising ways: it’s not just the 3D cockpit. It’s systems logic, displays, navigation computations, flight management, custom autopilot behavior, failure simulations, and high-frequency updates that must all stay in sync.

Real-time integration accumulates error. If the math becomes too stiff or unstable—especially near stalls, high angles of attack, or ground contact—the simulation can diverge into non-physical oscillations. To prevent that, developers add smoothing, damping, and guard rails.

Purists sometimes dismiss these as “fake,” but without them the simulation can become uncontrollable when frame times spike or noisy consumer inputs arrive. In practice, stability techniques are not the enemy of realism—they’re often what allows a simulator to remain usable while still capturing the right trends and responses.

All of this ties back to hardware reality: the simulator has to remain flyable across a wide range of PCs while producing consistent behavior under changing performance conditions.

Early consumer simulators, particularly those in the Microsoft Flight Simulator lineage, were built in an era where CPU cycles were scarce and memory was extremely limited. That environment strongly favored simplified aerodynamics and table-driven approaches, where developers stored coefficient curves and interpolated between them.

Those choices weren’t about cutting corners—they were about engineering reality. With limited processing power, developers could either run a stable model at a reasonable update rate or attempt something more complex and fail to maintain responsiveness. Table-driven models also made aircraft behavior highly tunable, which was essential when many aircraft types had to be supported without custom code for each one.

It’s also worth saying clearly: lookup tables are not inherently unrealistic. Real aircraft performance data often comes in tabulated form—pilot operating handbooks, certification reports, wind-tunnel results, and coefficient charts. A table-based model can be very accurate within the range it was designed for. Its limitations usually show up when the aircraft is pushed outside that envelope or when complex coupling effects demand more than scalar coefficients.

Older model architectures get criticized because they can feel less dynamic at the edges of the envelope. But many classic add-ons proved that strong data and careful tuning can produce aircraft that match published performance numbers and standard operating technique surprisingly well. The trade-off is that it’s often easier to match targets (climb rate, stall speed, cruise power) than to match behavioral nuance (how the aircraft talks to you approaching stall, how it responds to gusts, how it settles in ground effect).

Modern consumer simulators generally fall into three broad categories. In practice, many engines blur these lines, but the distinctions still help explain why different platforms feel the way they do.

Table-based models often shine where documentation exists. If you have reliable performance charts across weight, altitude, and temperature, a table-driven approach can match those outcomes tightly. The hard part becomes creating believable transitions between regimes—like pre-stall buffet, stall break, wing drop tendencies, and recovery behavior—where simplified coefficients may not capture the physics that generate the sensations pilots rely on.

Blade-element style approaches can feel “alive” because the model responds to changes in geometry and local airflow rather than following a single set of precomputed curves. This can be particularly convincing in situations like crosswind landings, propwash effects, or asymmetric configurations—provided the underlying assumptions and tuning are sound.

However, these models still need empirical knowledge. If the airfoil data is incomplete, if the simulator’s stall model is simplistic, or if the damping and control effectiveness logic isn’t well calibrated, the result can be just as wrong—only wrong in a more dynamic way.

Hybrids are pragmatic. They acknowledge that some aspects of the flight envelope are best anchored to real-world data, while other aspects benefit from more granular modeling. When implemented well, a hybrid approach can produce both accurate performance targets and convincing “between-the-lines” behavior such as trim changes, gust response, and configuration effects.

No single philosophy guarantees realism. Data quality, tuning discipline, numerical stability, and implementation details matter just as much as the headline method.

At runtime, the simulator repeatedly performs a sequence that looks roughly like this:

This is why it’s misleading to treat “flight model realism” as a single module. The experience is the interaction of multiple loops: flight dynamics, engine model, control filtering, and autopilot logic. A weak link anywhere in that chain can produce behavior that users blame on “physics,” even if the aerodynamics themselves are fine.

A quick reality check (what we see when testing across sims): When you fly the same aircraft type through the same profile—same weight, same approach speed, same wind—most “big” differences show up near the ground (flare/ground effect/ground contact), during gusty weather (how turbulence is applied), and in control feel (input filtering and frame pacing). Cruise and basic performance targets often agree more closely than forum debates suggest.

“Feel” is an emergent property. You don’t experience equations directly—you experience their filtered result through controls, visuals, sound, and ground interaction.

This is why debates about which simulator is “more accurate” often go nowhere. What you’re really comparing is a stack of design decisions, not just a flight model algorithm.

Many realism debates are actually propulsion debates. Piston engines generally require believable manifold pressure behavior, propeller efficiency across speed, mixture effects, and torque/P-factor. Turboprops often need spool and governor logic that behaves plausibly during rapid power changes. Jet aircraft typically need realistic thrust lapse with altitude, spool delay, and idle-to-go-around timing that matches expectations.

If engine response is too immediate, the aircraft can feel “gamey.” If it’s too sluggish, it can feel underpowered. If thrust and drag aren’t balanced well, pilots will complain about floatiness, climb performance, or the need for unrealistic power settings—even if the lift model itself is solid.

Most simulators agree closely during normal flight. The hard problems appear at the edges of the envelope.

Paradoxically, greater physical fidelity can sometimes feel less believable on a desktop. Without matching control forces or motion cues, high-frequency realism may read as instability.

Stalls and spins are difficult because they aren’t just “low speed.” They are a change in the airflow regime. Lift does not decrease smoothly forever; separation changes the relationship between control input and aerodynamic response. Wings may stall asymmetrically. The tailplane may be blanketed. Recovery depends on inertia, yaw damping, and control effectiveness—all of which must be modeled consistently.

Some consumer sims choose to keep behavior more docile near stall to avoid frustrating casual users. Others attempt to model more aggressive departures and recoveries. Either approach can be defensible depending on product goals, but it explains why users can have wildly different perceptions of “realism” based on how often they explore the edge of the envelope.

The transition from approach to touchdown is where many sim complaints concentrate, because it blends aerodynamic modeling with camera cues, frame pacing, and ground contact physics. Ground effect reduces induced drag and changes lift distribution close to the surface. Real aircraft often feel like they “want to keep flying” when you flare correctly, but the exact character varies by design.

If a simulator overdoes ground effect, aircraft can hover unrealistically. If it underdoes it, landings can feel like the aircraft gets “sucked in” despite a proper flare. If the tire and suspension model is simplistic, even a good flare can end in a bounce that feels disconnected from the approach.

Flight models don’t exist in a vacuum. Whether a simulator uses tables, blade elements, or a hybrid approach, it still needs data to define how the aircraft behaves. This is where realism often succeeds or fails.

High-end professional training devices may have access to extensive proprietary data. Consumer add-on developers often rely on publicly available charts, educated inference, and iterative tuning—especially for modern airliners where detailed aerodynamic data is not publicly distributed.

A flight model can be tuned to hit the correct cruise speed at a given power setting and still feel wrong in turns, turbulence, or trim transitions. That’s because pilot workload and handling qualities depend on the slopes and interactions between variables, not just the endpoints.

When pilots talk about an aircraft being “stable,” they may be describing how strongly it returns to a trimmed condition after a disturbance. When they say it feels “heavy,” they may be describing roll acceleration and damping. These qualities come from moments, inertia, and control effectiveness—not just lift and drag values.

Aircraft add-ons can dramatically change handling, but they still operate within the host simulator’s core architecture.

Add-on quality varies because flight modeling is part science and part craft. Two teams might have access to different reference material, different pilot feedback, and different tuning philosophies. One team may prioritize matching published performance charts. Another may prioritize handling qualities and energy behavior. Ideally, you want both—but trade-offs happen, especially under the constraints of a consumer platform.

It’s also common for an add-on to improve one part of the experience while exposing limits elsewhere. A highly detailed engine model might reveal shortcomings in the base simulator’s propwash or turbulence logic. A realistic landing flare model might clash with a simplistic tire model. These interactions are why aircraft can feel dramatically different even within the same simulator.

If you want to judge flight model credibility, it helps to move beyond vague impressions and look for consistent patterns. You don’t need to be a test pilot to do this—you just need repeatable scenarios.

No consumer sim will match everything perfectly, but a good flight model tends to be internally consistent: changes in configuration, weight, and atmosphere produce the expected trends, and the aircraft behaves coherently across different regimes.

Even the best consumer simulators face unavoidable constraints.

The right question is rarely “Is it perfect?” but “Is it consistent, stable, and credible within the envelope it’s designed to simulate?”

It’s tempting to compare home sims to full-flight simulators or advanced training devices, but their constraints and goals are different. Professional devices may use highly detailed proprietary data, specialized hardware, and strict validation procedures. They also include motion platforms, accurate control loading, and calibrated visuals—key sensory elements that desktop sims typically lack.

Consumer simulators can still be excellent learning tools for procedures, navigation, and cockpit flow. But when it comes to “feel,” a desktop sim is always translating reality through limited inputs and outputs. That translation is where compromises show up.

Perfect realism is unattainable in consumer flight simulation because the problem extends far beyond aerodynamics. It includes real-time computation, imperfect data, limited hardware, human perception, and numerical stability.

Understanding those tradeoffs often improves enjoyment. It shifts the discussion away from buzzwords and toward how the simulator actually behaves when you fly it. That’s where flight modeling stops being marketing—and becomes engineering.

For most users, the most useful definition of realism is: the simulator produces the right relationships between inputs and outcomes. If you’re too slow on base, you should need more power. If you’re heavy and hot at high altitude, climb performance should suffer. If you flare too high, you should float and risk running out of runway. If you mishandle energy in a turn, you should feel it in airspeed decay. These are the relationships that make a sim valuable and credible.

A flight model is the collection of algorithms and data that compute an aircraft’s forces and moments in response to control inputs, configuration, and atmospheric conditions. It determines how the aircraft accelerates, turns, climbs, stalls, and reacts to turbulence in real time.

Most consumer simulators estimate lift and drag using simplified aerodynamic models. Depending on the platform, this can be done through precomputed coefficient tables, analytical calculations based on geometry and local airflow, or a hybrid approach. The simulator evaluates the aircraft’s state (such as angle of attack, airspeed, air density, configuration) and outputs forces and moments that get integrated forward in time.

Both can be realistic in different ways. The underlying method (blade elements vs tables vs hybrid) matters, but the quality of data, tuning discipline, engine modeling, control filtering, and ground physics often matter more. A well-developed aircraft in either simulator can be highly credible, and a poorly tuned aircraft in either can feel wrong.

When users describe “floaty,” they’re often reacting to a combination of factors: ground effect strength, drag modeling, stability damping, camera motion cues, control sensitivity, and frame pacing. Sometimes it’s aircraft-specific tuning rather than the core simulator. The best way to diagnose it is to test repeatable scenarios (weight, atmosphere, approach speed) and compare trends and energy behavior rather than relying on a single impression.

They can significantly refine it. Add-ons can alter aerodynamic coefficients, geometry definitions, engine behavior, and weight-and-balance characteristics, and some can inject custom logic to improve specific behaviors. But most still operate within the simulator’s core architecture for integration, ground contact, and turbulence generation.

Because ground handling involves tire dynamics, suspension behavior, braking, slip angles, caster effects, and discrete contact resolution—often under variable frame timing. Small inaccuracies can produce big subjective differences: an aircraft that feels too “icy,” overly grippy, or prone to unrealistic bouncing. Ground physics is a separate discipline from aerodynamics, and it’s one of the most challenging areas for real-time consumer simulation.

Yes. Even when the physics tick rate is separate from rendering, frame pacing affects input sampling, camera motion, and perceived smoothness—especially near the ground or in turbulence. Stable performance can make an aircraft feel more controllable and “connected,” while stutters can make a good model feel unpredictable.

Because full CFD is computationally expensive, complex to set up, and difficult to run interactively at the update rates required for smooth flight. Consumer simulators prioritize real-time stability and broad hardware compatibility. Many use approximations that can still be highly credible when combined with good data and careful tuning.

Start with input calibration and control curves, then use aircraft-appropriate hardware if possible (especially rudder pedals). Keep frame pacing stable, avoid extreme sensitivity settings, and fly by published speeds and procedures. The more consistent your setup, the easier it is to judge what the flight model is actually doing.

Upgrade Microsoft Flight Simulator, FSX, P3D & X-Plane in minutes with our curated file library packed with aircraft, scenery, liveries, and utilities.

Ready to upgrade your hangar?

Browse the free file library

0 comments

Leave a Response